%20small.jpg)

The new Brimbank Aquatic and Wellness Centre in north-west Melbourne is pretty cool, and also pretty warm – or so say many of the 1.3 million people who have visited since it opened late last year.

It has a massive gym, an indoor Olympic-sized pool, and a water park children's play area complete with two water slides.

But on the wet Wednesday morning I toured the centre, the main attraction was on the roof, underground, and outside in the pouring rain - a massive industrial scale heat pump which cools the gym and heats the pools.

Brimbank Council climate emergency coordinator David Collins says the device has saved them an estimated $300,000 - $500,000 in gas and electricity costs compared to the original, gas-powered boilers – even though foot traffic at the new centre is triple that of the old.

Heat pumps are now common in residential homes – reverse-cycle air conditioners are actually heat pumps. Apartment and office buildings, meat works, and pools are now all applications where heat pumps are being put to the test in Australia.

Because of Australia's historical reliance on gas for heating, organisations like the Brimbank Council are at the cutting edge of commercial and industrial applications. And this means there is no template to copy and few experienced tradespeople to lean on – everyone is figuring it out together.

From next year though, locations like the Brimbank Aquatic Centre will begin sharing longer-term performance data. Jarrod Leak, the CEO of the Australian Alliance for Energy Productivity (A2EP), believes this will give other organisations the confidence to install large-scale heat pumps and replace gas - it will start to change hearts and minds.

"You'll see more confidence coming in the next few years with more expertise of how to completely change in one go," he told SwitchedOn.

"Brimbank is like a second-generation electrification solution, and it usually takes about three or four generations before people start really getting it right and that learning curve starts kicking in.

“It's not far away. We're seeing third generations getting designed and built now. Within two or three years within the aquatic centre industry, they'll have really nailed it."

Perfect for pools

Heat pumps are like reverse cycle fridges.

“Just like your fridge moves heat from inside the fridge to the outside to keep things cool, heat pumps capture heat from the surrounding environment – the air – and upgrade it (increase the heat level) using a compressor," he says.

"The beauty of heat pumps is that, as well as being extremely efficient, they utilise waste heat and put it to work."

A huge amount of energy is used to heat and cool large commercial and industrial spaces. A 2019 report by the NSW Office of Environment found water and space heating account for about 90 per cent of the operating costs of aquatic centres.

Leak says heat pumps are particularly efficient for sub-50°C temperature heating, such as aquatic centres, and are four to eight-times more efficient than using a gas-fired system. Not only that, the cool air created when using a heat pump can also be used for space cooling in, for instance, a gym.

“Aquatic centres only require low temperature heating - pools are around 27°C - and nowadays often have a recreation or fitness centre that needs cooling whilst the pool needs heating so heat pumps are a really good fit,” says Leak.

In addition to having greater efficiency than gas boilers, electric heat pumps can utilise the generation from onsite solar PV systems to further reduces emissions.

“Heat pumps need to be a priority technology in government and business decarbonisation plans,” says Leak. "Heat pumps are… proven [technology] available here and now, but too often we see pie-in-the-sky technologies that are years away from commercialisation preferenced instead.”

Brimbank's new pool is almost entirely off gas

The $60 million Brimbank Aquatic Centre opened in September 2022 and was originally designed to be gas powered. In fact the contractor had been engaged, and the designs were set.

At the last minute a $1.53 million ARENA grant popped up and a late-stage switch was made to install a heat pump.

The whole system cost $8.1 million, partly due to the last minute decision to switch from gas, and partly due to the technical challenges of making a heat pump work in an electricity-heavy pool setting. The heat pump itself cost $2.1 million.

Today the centre is all electric, except for the backup gas boiler as a just-in-case for particularly frosty mornings. East Keilor, where the pool is located, can see temperatures down towards 0°C in winter. This can be a problem for heat pumps - which draw hot air from outside - if they’re not set up properly.

This year the gas boiler provided 1.4 per cent of total heating because of those temperatures, but Brimbank’s David Collins is hoping that by tweaking the system they may be able to nix the gas boiler entirely in 2024.

The centre's 1.4 MW heat pump consists of seven different condensing units, and works with an 88 KL thermal energy storage system, supported by 500 KW of rooftop solar PV which generally provides 14 per cent of the pool's energy needs – although not during a downpour.

Our tour started on the first floor in the Heating, Ventilation and Air-conditioning room (HVAC), tucked in behind the gym and large exercise rooms. It contains all the infrastructure needed to move the heated and cooled air throughout the centre.

Metal stairs led to the roof with a viewing platform out over the rooftop solar system, and the heat pump dedicated to domestic hot water.

Down on the ground floor, on the same side of the building as the upper-story plant, is the main plant room where the control panels sit to control the rack of heat pumps outside. The basement is where the heat exchangers, water quality, and dosing equipment are housed.

Adaptation key in move from gas

Heat pump technology has been around since the 1960s and is widespread in countries like New Zealand and in Europe.

For every gigajoule (GJ) of electricity used they can generate 4 GJ of heat. Compare that to a gas boiler which needs 1.18 GJ of energy to create 1 GJ of heat.

In Europe, industrial-scale heat pumps are used to heat entire cities. Stockholm, in Sweden, has a 215 MW installation that is made up of seven heat pumps – two 40 MW and five 27 MW devices. Gothenburg in Germany has a 160 MW system made up of four units, two of which are a massive 50 MW each.

In Australia where gas has been the norm, industrial or commercial heat pumps require some adaptation on the part of users. For example, gas boilers are normally set to heat water to 80°C which then travels through pipes which heat the air.

But getting a heat pump to operate at this temperature is inefficient – their optimal range is 50-60°C, although new designs in the last five years have lifted that threshold to 90°C.

Which means that to heat a large space, such as an office building, the system needs to be switched on earlier in the day. Leak says office buildings should be running tests over winter with gas boilers set to lower temperatures, to see where their users' comfort thresholds are.

Furthermore, heat pumps need a lot more space – about five times that of a gas boiler - and some buildings simply won't be able to accommodate that.

However, with some clever thinking such as converting the corners of underground carparks, or cannibalising sections of office space, many buildings will be able to install large heat pumps.

Heat pumps are also heavy – about 10 times the weight of an equivalent gas boiler. The Brimbank Aquatic Centre was purpose-built so its rooftop has been designed to take the extra weight, but the roofs of most buildings are not designed to add several tonnes of weight.

Meatworks

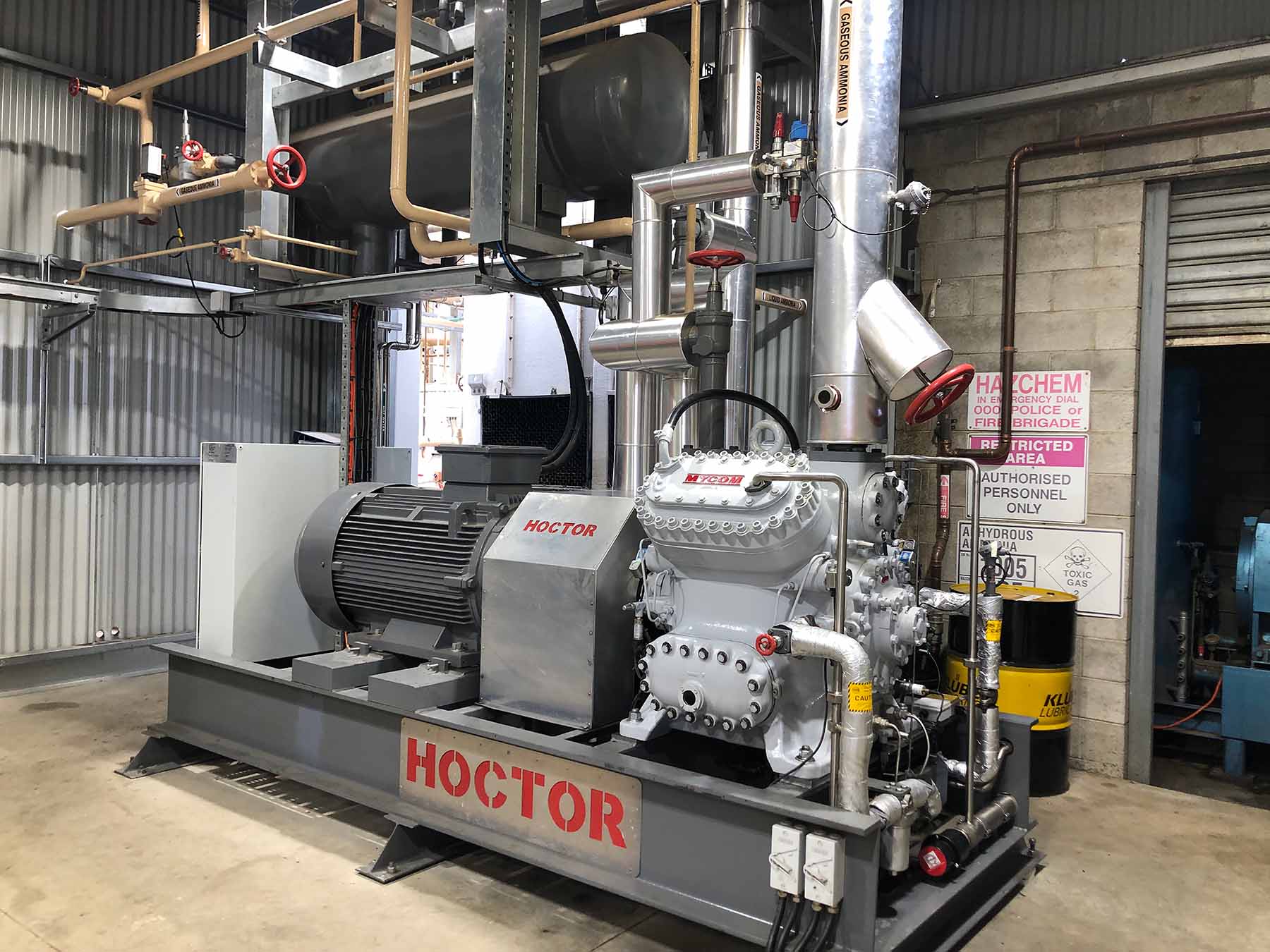

Other industrial applications, such as the heat pump installed at Hardwicks Meat Works in Kyneton, in Central Victoria, have had to build a highly bespoke system to keep the site cool.

It uses the site's 2.5 MW solar farm and a 2 MWh battery storage system, the existing 150,000 litre hot water storage tanks, and an oil heat recovery system. Like the Brimbank Aquatic Centre, Hardwicks has a gas backup. They’ve had to integrate it all into the ammonia refrigeration plant.

The abattoir's system was retrofitted and came online in January 2023, with a goal to reduce gas use on site by 75 per cent. However, the actual monthly gas reduction is around 80 per cent, thanks to the thermal storage tanks.

A "lessons learned" report from ARENA, which funded a third of the $2.57 million project, notes that installing a 1 MW heat pump into an existing operation takes time.

It also noted that conducting a solid pre-feasibility study could have identified the need for power line upgrades sooner, which was almost half the total cost.

Such a study would have meant they didn’t overlook the regulatory requirement for ammonia detection near electrical equipment. The meat works had to add ammonia detection, automated electrical shunt trip and mechanical ventilation.

Furthermore, thanks to a growing business the abattoir began using a lot more water than when the initial three-year study was conducted and commissioning for the heat pump was delayed a few times because they ran out of water, says project manager Mark Hardwick.

Today, they're trying to optimise the system, which shuts down for two days over the weekend and effectively has to heat a lot of cooled water on a Monday to get up and running again for the week.

Currently Hardwick’s operates for about 22 hours a day, five days a week. “The more we can get that heat pump to run, the more we save on the gas,” says Hardwick.

"We've still got some cold water going into the system so we're trying to get that out to keep the system running 24 hours a day. But having the double shift helps, and having the inventory that we can store water helps as well so we can actually keep the machine running when the demand on the system is not as great… which makes the economics of the project better."

A bit more cash from government would help

Australia is operating on a carrot rather than a European stick approach when it comes to switching from industrial gas to heat pumps.

The heat pump systems at the Brimbank Aquatic Centre and Hardwicks Meatworks were made possible with ARENA funding. Rebates are also available for select brands.

Jarrod Leak says governments need to fund studies to show commercial building owners and industrial sites that heat pumps are a possibility.

"They seem to be struggling to come up with the $30,000, maybe up to $100,000, for a really detailed study for an industrial facility," he says.

A2EP has helped some 30 companies get funding from ARENA for studies which look at how to integrate heat pumps with existing processes and get the most out of things like heat recovery, or maximise the coefficient of performance (COP), which is a measure of how much electricity you need to get heat.

Leak also says changing the way renewable energy certificates are calculated in Victoria and NSW needs to be changed to further incentivise building owners to quit gas.

Currently companies such as Hardwicks Meatworks aren't eligible for certificates even though they've reduced gas use by 80 per cent. This is because the extra power they are drawing from the grid is calculated as having a percentage of fossil fuel generation.

-LEAD.png)